On Email as Poison

And whether or not there is an antidote

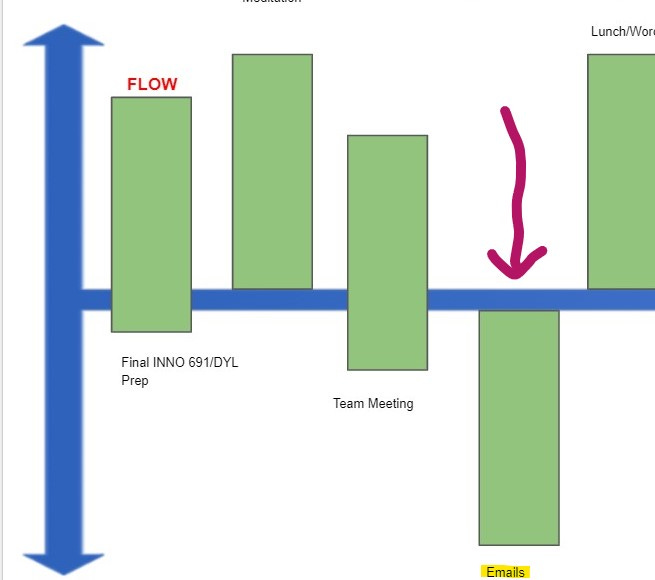

I recently did an energy mapping exercise with my students as part of a class I’m teaching this semester. If you aren’t familiar with this, it basically involves thinking over your day, creating a timeline of the major things that you did, and then visually ranking them as to whether they gave you energy or drained your energy. Here’s mine, as an example:

The course I’m teaching is centered around using a design thinking framework to help graduate students think though the next steps in their lives, both for their remaining time in school and post-graduation. In classes where self-reflection is so paramount, I’m a firm believer in a certain amount of self-disclosure on my part, as the instructor— the idea that I’m not asking students to do something I haven’t done or thought about myself. It also sets the tone of the classroom being a safe place to share. Rooted in this pedagogy, I didn’t think twice about sharing the image above with my class.

Now, you may not have immediately noticed this, but as people who communicate with me via email quite a bit, several of my students honed in on this particular bar, right away:

My immediate first thought was, oops-well, this is not my finest moment, followed quickly by and . . . so this is where the whole self-disclosure thing falls off the rails as I’ve now made this whole class of students feel bad about emailing me with questions. This obviously, was totally, not my intent. And yet, it is an honest assessment, email is a huge energy vampire for me.

So in attempt to offer some additional perspective, and not make this seem like an off-limits channel for contacting me, I went on to explain that it’s not the people emailing me that are an energy drain, I’m happy to help the person emailing me. The energy drain comes from both the sheer volume of messages I receive and a heavy dose of guilt around how long it often takes me to reply. Luckily that explanation resonated and my students haven’t stopped reaching out with questions (though I did get a very kind postscript on one just after class, hoping the message wasn’t too much of an energy drain).

As with many experiences that feel awkward in the moment, I later realized that something really important had come out of going a little deeper on this one. For years I’ve been lamenting, Gah! Email! If I could just get on top of my inbox, or I am just the worst at email. That little inbox number in the upper left hand corner of my email client (that for times of the year rarely dips below 100) haunting me in the middle of the night. Pausing for a moment to try to really explain why email is such an energy drain for me forced me get to the heart of why.

The first part I knew— the shear number. The second part surprised me a little— the guilt. Specifically the guilt about my response time. I’m not quite sure where it comes from. It might be rooted in a previous position I held where 24 hour response time was the gold standard (that I never hit). It might stem from my own deep people-pleasing and not wanting to have made someone feel less important, or have held up their work by not immediately responding to them. Likely it’s a bit of both. I’m still working on unpacking this one.

Which is why it was very timely that one of the messages upping the count in my inbox recently was an article titled: Higher Eds ‘Productivity Poison’- Cal Newport on Why Email Makes You Worse at Your Job and the Future of Remote Work. Which is the longest title ever, but honestly they had me at Productivity Poison because YES, YES, YES! That’s it. That’s part of the guilt. It’s either email or other projects. I can prep for class, work on the detailed schedule for a semesters worth of recruiting events OR answer email. But not both email and a project that requires my undivided attention at one time.

Newport explains this phenomenon of what constantly checking in on our inboxes (or Slack or Google Messenger or Teams or etc. etc.) does to our brains in the interview detailed in the article:

“… quick checks of inboxes also have a substantial neurological impact. If you’re quick checking once every six minutes, you’re in a perpetual state of significantly reduced cognitive capacity. And you’re going to get cognitive fatigue, which is why we run out of steam at 2 in the afternoon and give up on doing hard things. It’s productivity poison we didn’t know we were ingesting.”

Newport is a computer science professor at Georgetown University, who has written extensively on the effect of digital technology on the productivity of knowledge workers (not just those of us in higher ed). I loved his book Digital Minimalism for its non-preachy practical suggestions about putting guardrails around social media and I have many friends who have indicated his book Deep Work was equally impactful.

What I’ve enjoyed most about Newport’s work, including the answers in this interview, is his reminder that there is something bigger at play here. The idea that our brains aren’t equipped for the constant task-switching and that the autonomy we’re given in how to structure our time, sometimes leaves us feeling endlessly pulled in a million directions. In other words, there are systems problems bigger than us that make it hard (read: impossible) to get through everything on our task lists. Adding in even more online time as we’ve transitioned to more remote work over the last two years, hasn’t helped:

“When it comes to knowledge work, the way we organize and assign and track and manage is quite haphazard. We tend to just throw things on people’s plates and figure things out on the fly. When we moved to remote during the pandemic, this haphazard approach spiraled out of control. We lost some of the productivity heuristics that we didn’t realize we’d been implementing: being able to grab someone in the hallway for two minutes, or seeing on someone’s face that sense of overload that makes you think twice before emailing them and saying, hey what’re your thoughts on this? Can you jump on a call? Could you work on this report? When we lost those heuristics, things really did spiral. And we got to this Kafkaesque place where we were on Zoom every hour of the day. Where we only talked about work and never had any time to actually do work.”

While the major benefit of this article landing in my inbox when it did was that it made me feel seen and less alone in my struggles and reminded me that my inability to keep up isn’t completely a personal failing— there was also one tip to tackle the overwhelm that felt particularly helpful. The idea of instituting office hours.

Typically thought of as a structure unique to professors at universities, Newport suggests, that we could all try blocking time for people to stop by (literally or through an open Zoom room) with questions that just take a moment to answer. Things like setting a time for a meeting or getting quick feedback on something you’re planning. He suggests it’s a way to help stop the endless email loops and replicate the concept of popping by a co-workers desk to ask a quick question (except better, because it’s a set aside time when you won’t be interrupting them).

I think it will take a while to habituate to this— but I’m going to give it a go, with a couple mornings a week for colleagues to drop by if I’m not getting back to them quickly enough, as well as a time each week for students to do the same. My hope is that providing this space will address some of my guilt around response time by providing another way to ask questions.

And while I’m excited to give this concrete step a try, I suspect the true solution to my email overwhelm may lie closer to the closing words in the introduction to Oliver Burkeman’s book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals:

The day will never arrive when you finally have everything under control— when the flood of emails has been contained; when your to-do lists have stopped getting longer; when you’re meeting all your obligations at work and in your home life; when nobody’s angry with you for missing a deadline or dropping the ball; and when the fully optimized person you’ve become can turn, at long last, to the things life is really supposed to be about. Let’s start by admitting defeat: none of this is ever going to happen.

Burkeman goes on to proclaim that this admission of defeat, this fact that it’s never going to get done is— “excellent news.” Which I’m imagining the rest of the book will fully dive into (full book report here when I’m done), but I’m liking where I think it’s headed, which seems to be toward the idea that maybe all this time in my inbox might not be the best use of my precious moments.

Toward a paradigm shift.

But I’ll start with those office hours — now to send an email my colleagues and students about them . . .

Things of Beauty

Just a few things that felt particularly soul-nourishing recently (or maybe just made me smile).

Loving Kindness Meditation feels really important and resonant to me right now. Here is one I really like.

I’ve really been enjoying the series that Caroline and Jason Zook are doing over at Wandering Aimfully about embracing your authentic self in all aspects of your business. This particular article about social media was a favorite. (And I’m enjoying keeping up with their travels in Europe.)

Speaking of Europe — Emily in Paris. This has been my go-to, just for total fun show in February and I just finished season two. That cliffhanger… I mean I know what I want her to do and what I think she is actually going to do. Are you watching? Do you have thoughts?

More daffodils! These are from my parent’s garden:

Would love to hear from you! How are you tackling your inbox and or inbox-related-guilt these days? And/or What are the tiny beautiful things in your world? (Or you know, what’s your take Emily’s next move, that’s cool too!)

Postscript

The class I’m teaching is based on this philosophy which I took a training for educators about with Stanford’s Life Design Lab last summer (highly recommend!).

Cal Newport talks about a lot of the same themes as the article above in this podcast. Sharing this since I realize the link above requires you to create a free account with The Chronicle of Higher Education (side note: if you happen to be university affiliated, you should be able to log in to your university’s library site and access without creating an account).

Oh, I could so relate to this! I've completely given up on email, and mostly work to catch all the valuable emails among the dust and ads. I've read about tracking time before, but your energy graph is fascinating; I think I'll try that myself, too. Thank you for the idea! And the comments below were helpful, too; so many good ideas. I think you hit a nerve. :)

I love this essay, Mary Chris! I never thought to map out a day to see what parts or projects drain my energy and what nourish my energy. Instituting "office hours" is brilliant. I think that almost everyone feels like they're constantly behind in some way, and it can be daunting! Especially when comparing ourselves to others and how their lives "seem" to look. And on a side note: I admittedly love watching Emily in Paris (the first season was kind of bad, but the second season was so good).